In an age where speed and efficiency define success in business, the role of a truck driver in running an urban delivery service has never been more critical. Essential to the operations of manufacturing, distribution, retail, and even construction sectors, these drivers manage not only to deliver goods but also to bolster the economy and fulfill logistical demands. This article delves into various aspects of their operations—from financial insights, like determining the break-even point, to their significant impact on local economic activities and the challenges they face in navigating logistics. Each chapter will build upon this foundation, presenting a comprehensive view of how a single truck driver can effectuate change and sustain businesses across various sectors.

Miles, Margin, and Momentum: The Hidden Calculation Behind a City Delivery Service

Dawn breaks over a southern city, where the streetlights still burn pale orange against the horizon and a single pickup truck hums to life in a quiet alley. The driver sits behind the wheel, a coffee cup steaming in the cupholder, eyes scanning a route that threads through neighborhoods, small businesses, and late-rippling warehouses. The bed is empty today but ready, not because the jobs will materialize out of thin air, but because the driver has learned to make opportunity appear with a precise blend of discipline and grit. He is not merely delivering packages. He is testing a model for value in the city’s ecosystem: a small delivery service run by one person, powered by a careful balance of fixed costs, variable expenses, and a price point calibrated to the market’s demand. In that balance, the math is not abstract; it is a compass that points to the exact moment when effort becomes profit.

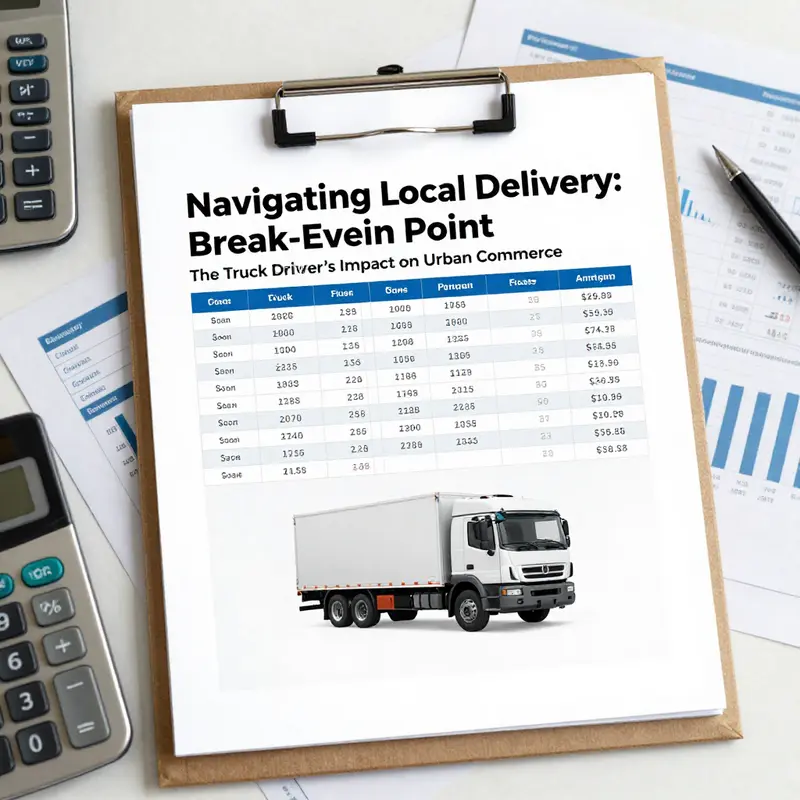

At the heart of this model lies a straightforward yet telling ledger. The startup costs stood at $2,500. That figure is not a marginal detail; it sits at the origin of every future delivery’s contribution to the bottom line. It is the initial bet on reliability—on a truck’s reliability, on a route’s predictability, on the driver’s own stamina to complete the daily tasks without compromising safety or service quality. Then there is the ongoing cost of each delivery, a clean line item of $4.00 per run. Gas, wear and tear, maintenance—these are the engine of the figure that will accumulate with every mile traveled and every stop made, every handoff to a customer or to a warehouse dock. The pricing side is equally clear: $6.50 charged to the customer for each delivery. The difference between what is charged and what is spent to fulfill the demand is where the work earns its living. In this setup, the profit per delivery crystallizes as $2.50: a simple arithmetic truth, but one that carries a heavy amount of real-world consequence. It is not merely profit on paper; it is fuel in the tank for the next mile, the next handoff, the next late-night phone call when a route must be adjusted because a loading dock opens late or a customer shifts a preferred delivery window.

The simplest way to understand when the business becomes sustainable is to picture the equation revenue equals cost, but with the numbers anchored in daily practice. Revenue per delivery is $6.50, and cost per delivery is $4.00. Subtracting the variable cost from the revenue yields $2.50 in gross contribution per delivery. To recover the fixed start-up investment of $2,500, you divide that fixed cost by the per-delivery contribution: $2,500 / $2.50 = 1,000 deliveries. In other words, once the truck has completed one thousand deliveries, every additional delivery pushes net profit upward, unassisted by that initial capital outlay. It is a stark reminder that the economics of small-scale logistics hinge on volume as much as on price, and that profitability is not a single moment but a cadence—an accumulating rhythm of deliveries that eventually converts a hopeful enterprise into a working business.

The notion of reach matters as much as the math. For a single driver, that cadence is a function of schedule reliability, customer trust, and the city’s geographic layout. The driver must cultivate a steady stream of business to achieve the required volume, and that means more than simply driving efficiently. It means building a reputation for punctuality, careful handling of goods, and transparent communication when delays occur. It means developing a predictable rhythm for that daily route, optimizing the sequence of stops to minimize backtracking and fuel burn, and learning the real costs hidden in every trip—traffic, parking time, waiting at docks, and the sometimes unglamorous moments of restocking or adjusting protective packaging. The per-delivery figure of $4.00 is not just fuel and wear; it includes the cost of keeping the truck ready for the next stop, the tires that grip the road through rain or heat, and the occasional replacement part that keeps vehicle downtime at bay. In that sense, the number is a mirror of the broader realities of last-mile logistics in a busy city.

What does this imply for the driver’s day-to-day life and for the city’s economy? It means that the first few months, even with efficient routing, will feel like a test of patience and stamina. If the driver can complete, say, fifty deliveries in a typical week, the break-even point of one thousand deliveries translates into roughly twenty weeks of full-time operation, assuming constant demand and no unplanned downtime. If the workload averages closer to twenty-five or thirty deliveries per week, the horizon shortens markedly, and the prospect of profitability approaches sooner rather than later. The reality is, of course, that demand fluctuates. Weather, the local economy, and the cadence of business hours in a city can tilt the pace of deliveries in one direction or another. The driver must be prepared to adapt—scaling up during peak seasons, trimming the schedule when a dock is slow to unload, or shifting to more recurring customers who offer predictable lanes. In short, the math provides a target, but the route to profitability is paved with resilience, flexibility, and customer-centric service.

This is not merely a private enterprise; it sits inside a broader logistics framework that keeps a city moving. The driver’s success depends on the trust of clients who see him as a dependable extension of their own operations. When small businesses become regular subscribers to a single, reliable delivery service, they gain more than the convenience of punctual arrivals; they gain a partner who understands the timing of their supply chain. The city’s market becomes a living laboratory for lean operation: fewer trips wasted, better route planning, and higher service levels. In this way, the practice of running a one-person delivery service illuminates a larger principle evident across the industry—that scale matters, but so does precision. The balance of fixed and variable costs means that every mile matters; every delivery is a micro-investment that either earns back the initial capital or nudges the business into broader profitability.

As with many drivers who undertake similar ventures, there is an element of endurance, as well as strategy. The personal costs can be steep—long hours, time away from family, and the risk of cumulative wear on both vehicle and schedule. Yet there is also a story of professional autonomy that resonates across the trucking world. The ability to set one’s own hours, negotiate a fair price with customers, and grow a business from a single vehicle to a more expansive fleet is a narrative mirrored in many cities. It speaks to a sector where hard-won experience, careful cost management, and customer loyalty intersect to create a viable path for small operators in a landscape dominated by larger logistical networks. The driver in this city embodies that tension: balancing the discipline of a startup accountant with the improvisational skill of a seasoned courier who knows every road, every dock, and every customer’s preference.

In reflecting on this model, it is worth tying the discussion to a broader literature on the economics of trucking and last-mile delivery. The thread of cost control, price setting, and demand management runs through many analyses of transportation and logistics. Yet the distinctive element here is how a single operator translates that economics into practical routines—how fixed costs, variable costs, and revenue per delivery are not abstractions but daily realities that shape decisions about routes, staffing, and investment. The city, with its mix of short trips and tight scheduling, exposes the delicate balance between efficiency and reliability. For readers curious about how such patterns fit into larger industry dynamics, the concept of economic trucking trends helps situate this microentrepreneurial effort within macro-level forces of transport, infrastructure, and market competition.

This lens also invites consideration of how similar operators elsewhere might approach their own break-even thresholds. If a driver starts with a larger startup fund, the margin per delivery might shrink or expand, depending on the price point and the fixed cost already incurred. Conversely, a driver could negotiate a higher per-delivery charge by offering enhanced service features—careful handling, guaranteed delivery windows, or real-time updates for customers. Each adjustment shifts the break-even equation, compressing or extending the path to profitability. The core discipline remains constant: know the unit economics, monitor the route performance, and preserve the flexibility to pivot when demand shifts or new constraints appear. The phenomenon is not unique to this southern city; it echoes across diverse urban markets where solo operators test the viability of a lean, customer-focused delivery service against the fixed realities of capital outlay and maintenance.

For readers seeking a broader, more formal grounding, the experience described here aligns with widely used business guidance on estimating startup costs and planning for transportation and logistics expenses. It is instructive to review those frameworks alongside the micro-narrative of a single driver who turns miles into value. The hard math—the break-even calculation, the profit per delivery, and the cumulative effect of recurring demand—serves as a practical counterpart to theory, illustrating how the abstract becomes actionable in the city’s street-level economy. In the end, the truck’s engine is a metaphor for the enterprise: it thrives on momentum built one delivery at a time, and it relies on the steady cadence of customers who trust a driver to get the job done right on time, every time. The chapter leaves us with a simple but powerful takeaway: profitability for a small, city-based delivery business is as much about rhythm and reliability as it is about price and fuel economy.

External resources for broader context can deepen this understanding. For a more extensive overview of how start-up costs are estimated and managed in transportation and logistics, see the SBA guide on estimating startup costs: https://www.sba.gov/business-guide/plan-your-business/estimate-startup-costs.

Breaking Even on the Road: How Many Deliveries a City Driver Needs to Cover Costs

Financial balance on a daily route

When we translate a truck driver’s operation into simple math, the questions become clear. How many drops will cover the start-up investment? How many more are needed to turn a steady profit? For this driver, the core numbers are straightforward: a one-time start-up cost of $2,600, a variable cost of $1.50 per delivery, and a charge of $4.00 for each completed delivery. Let x represent the number of deliveries. The total cost is 2600 + 1.50x. The total revenue is 4.00x. Setting revenue equal to cost gives a single equation that answers the primary question: when does the business break even?

Solving the equation 4.00x = 2600 + 1.50x yields x = 2600 / (4.00 – 1.50) = 1040 deliveries. Reaching 1,040 deliveries means cumulative revenue equals cumulative cost. Every delivery beyond that point contributes $2.50 to profit, because each delivery brings in $4.00 while costing $1.50 to execute. This difference, the contribution margin, is the practical lever for profitability.

Understanding what 1,040 deliveries implies in operational terms makes the number actionable. If the driver aims to break even within a year, 1,040 deliveries divide into accessible daily targets. Over 52 weeks that is 20 deliveries per week. If he works five days each week, the target becomes four deliveries per day. On a six-day schedule it falls to roughly 3.3 deliveries per day. These are modest daily volumes for an urban delivery service. The tightness of the target depends on route density, package size, and stop time. In dense urban neighborhoods, four stops a day may be conservative; in sprawling suburbs, the same stops could require far more driving time.

The break-even formula also shows why marginal improvements matter. The denominator in x = Fixed / (Price – Variable) is the per-delivery contribution margin. Small changes to either side of that margin change the break-even point significantly. For example, a variable cost reduction from $1.50 to $1.25 per delivery lowers the required deliveries to about 946. Raising the charge to $4.50 per delivery reduces the break-even count to around 867. Cutting fixed costs to $2,000 pushes the threshold down to 800 deliveries. Each of these moves has trade-offs: cost reductions may require upfront investment or operational change, and price increases can affect demand.

This sensitivity suggests a clear set of operational levers. First, increase the contribution margin. Techniques include negotiating bulk contracts, adding surcharges for urgent or oversized deliveries, and offering subscription packages to stabilize volume. Second, reduce variable costs. Fuel management, preventive maintenance, efficient routing, and optimized load planning all lower per-stop expenses. A small decrease in fuel or maintenance cost offers outsized benefits for the break-even calculation. Third, reduce fixed costs where practical. Leasing equipment rather than buying, delaying nonessential upgrades, or sharing storage can trim the upfront burden.

Route planning deserves emphasis. Each mile saved is both a cost and time reduction. Consolidating nearby stops into one loop raises delivery density and lowers per-delivery fuel and wear. Using simple scheduling strategies—batching deliveries by neighborhood, timing runs to avoid peak congestion, and prioritizing high-density windows—improves throughput without more hours on the road. Telemetry and basic route optimization tools can return measurable savings, especially when fuel and time are constrained.

Volume-building strategies matter because fixed costs remain sunk until recovered. Landing a steady stream of business from a handful of local retailers or service providers smooths daily variability. Contracts that guarantee a minimum volume can be structured with tiered pricing, offering slightly lower per-delivery fees in exchange for guaranteed volumes. Those agreements raise cash predictability and make it easier to plan for maintenance and growth.

It helps to model revenue and profit scenarios. At 1,200 deliveries, the driver’s total revenue is $4,800. Total cost equals 2600 + 1.50 * 1,200 = $4,400. Profit stands at $400. At 1,500 deliveries, revenue reaches $6,000 and costs $4,850, yielding $1,150 in profit. These quick checks demonstrate how additional deliveries translate directly to cash flow once the break-even point passes. They also show the relative pace of recovery. Profit grows linearly with volume because the contribution margin per delivery remains constant.

Profitability, however, is not solely a function of volume. Operational resilience matters too. The driver must fund periodic maintenance, carry insurance, and set aside capital for unexpected repairs. Putting a fixed percentage of each delivery’s contribution into a maintenance reserve keeps the truck reliable and reduces the risk of sudden downtime. Similarly, taxes and licensing costs require planning. Achieving break-even on paper does not automatically mean comfortable cash flow after taxes, fees, and unplanned expenses.

Labor and personal costs are another component often overlooked in simple models. Long hours reduce quality of life and can increase indirect costs through fatigue-related errors or slower deliveries. The example of long-haul workers illustrates the human side: reliability often comes at the expense of personal time. For a city-based driver, pacing the schedule to avoid burnout is an operational imperative. Sustainable delivery targets support consistent service and reduce churn in customer relationships.

There are strategic moves beyond tightening costs and routing that change the economics of the business. Diversifying services to include white-glove delivery, scheduled recurring pickups, or same-day options allows the driver to charge premium rates. Partnering with local merchants or joining an informal network with other small operators can increase load factors and reduce empty miles. On the investment side, upgrading to more efficient vehicles may carry a higher upfront charge but lower long-term variable costs, reshaping the break-even horizon.

Market context also influences the break-even landscape. Industry-wide shifts in demand, consumer expectations, and fuel prices affect both revenue potential and variable costs. Monitoring local demand trends keeps pricing competitive and helps to anticipate when adding capacity is sensible. For further reading on broader industry trends that frame these decisions, see this analysis of economic trucking trends.

Finally, think of break-even as a planning milestone, not an endpoint. Reaching 1,040 deliveries means the business covers historical outlays and per-delivery costs. Beyond that, every incremental delivery builds capital that can be reinvested. The choices about reinvestment shape the next stage: marketing for more volume, upgrading equipment, or diversifying services. Each option changes cost structure and future break-even calculations.

The arithmetic behind break-even is simple. The operational choices behind the numbers are not. A city delivery service that understands its fixed costs, actively manages variable expenses, and focuses on route density and sustainable schedules converts a break-even threshold into a runway for growth. The driver’s short-term target—1,040 deliveries—becomes the basis for day-by-day decisions that balance income, time, and long-term viability.

For a primer on break-even analysis and the formulas used here, see the Investopedia guide on break-even analysis: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/breakevenpoint.asp

How One Local Delivery Driver Multiplies Economic Value Across a City

A single delivery business can alter how a neighborhood moves goods, money, and opportunity. Starting with a modest $2,500 outlay, a truck driver who charges $6.50 per delivery and spends roughly $4.00 per run reaches a clear financial milestone at 1,000 deliveries. At that point, revenue equals cost and profit begins. That simple break-even calculation—2.50 dollars of margin per delivery—frames a larger story about how a small logistics operation generates steady economic benefits across a city.

The arithmetic is straightforward. Fixed startup costs cover permits, basic equipment, and initial marketing. Variable costs include fuel, routine maintenance, and incidental supplies. Each completed delivery contributes a margin, however small, that accumulates into sustainable income. When the operator covers fixed costs, every subsequent delivery converts directly into earnings that can be spent or reinvested. Those decisions—how earnings are used—drive most of the local economic ripple effects.

First, consider direct support to local businesses. Many small retailers and food vendors cannot sustain their own delivery infrastructure. A dependable local carrier enables these businesses to reach customers beyond their storefronts. Faster local deliveries improve sales conversion and encourage more frequent purchases. For a corner bakery, the ability to offer delivery within a half-hour can mean serving office workers across the block. For a hardware merchant, timely deliveries to construction sites prevent work stoppages. When local firms increase revenue, they hire more staff, order more supplies, and expand operations—each action pumping demand back into the community.

Second, logistics services create jobs beyond the driver. Successful scaling often requires hiring additional drivers, warehouse assistants, or dispatch coordinators. Those roles are accessible and provide income that gets spent locally. A warehouse worker who earns wages will purchase groceries, pay rent, and use local repair shops. The driver’s relationship with service providers creates recurring business for fuel stations, independent mechanics, and parts suppliers. A single fleet of one to three vehicles can sustain a mini-network of associated service providers—an ecosystem that grows alongside the carrier.

Third, local procurement matters. When a delivery service buys supplies—hand carts, packing materials, storage racks, signage—they frequently source from nearby vendors. Those vendors, in turn, purchase inventory and services. This circular flow keeps money within the region. It reduces leakage to distant corporate supply chains and magnifies the multiplier effect: every dollar spent by the delivery operator supports additional rounds of local spending.

Fourth, improved delivery reliability raises consumer satisfaction and loyalty. Consumers who experience consistent, punctual service will order more often. Repeat business stabilizes revenue for both the carrier and local merchants. That stability encourages merchants to experiment with product offerings and expand their customer base. Entrepreneurs observing the success of a local carrier may launch complementary ventures—packaging design services, urban micro-fulfillment centers, or neighborhood courier startups—further diversifying the local economy.

The financial mechanics make these outcomes possible. With a profit of $2.50 per completed delivery beyond the break-even point, a driver who completes 1,500 deliveries annually would net about $1,250 after covering variable costs and fixed startup costs prorated across the year. Reinvesting a portion of that profit can accelerate growth. Purchasing a second vehicle or upgrading to a larger truck increases delivery capacity and opens new customer segments. Hiring an additional driver multiplies route coverage and reduces delivery times. Each expansion adds payroll, fuel consumption, and parts demand, all of which are met by city businesses.

Growth also strengthens tax revenues. As the carrier becomes profitable and hires staff, payroll and sales taxes increase municipal revenues. Those taxes fund local services—roads, public safety, and community programs—that support broader economic activity. Improved public infrastructure, in turn, reduces operational friction for logistics providers by shortening travel times and lowering vehicle wear.

Local delivery services also enhance urban resilience. When larger, national carriers face capacity constraints, local operators bridge gaps. During seasonal peaks, local drivers absorb overflow demand. In disruptions—severe weather, labor stoppages, or supply chain bottlenecks—local carriers often react faster because their operations are embedded in the community. This flexibility reduces downtime for local businesses, protecting incomes and preserving consumer access to essential goods.

However, growth brings trade-offs. Increased delivery traffic contributes to congestion and wear on city streets. Municipal planning must balance economic benefits with infrastructure maintenance and traffic management. Noise and emissions are concerns, particularly in dense residential areas. These challenges drive demand for mitigation services—route planning, driver training, and vehicle maintenance—which are additional local business opportunities.

Fuel and environmental costs push innovation. Operators who track per-delivery fuel consumption can optimize routes and schedules to cut expenses. Adopting smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles for last-mile runs lowers operating costs and reduces emissions. Electrification and alternative fuel options present long-term opportunities, though they may require higher upfront investment. Local drivers who invest in cleaner vehicles can reduce per-delivery energy costs and appeal to environmentally conscious customers, further differentiating their service.

Regulation and compliance shape how local carriers operate. Licensing, insurance, and safety standards impose predictable costs. Yet these rules also create markets for compliance specialists—insurance brokers, safety auditors, and training consultants—often based locally. When officials adopt policies that support small carriers, such as streamlined permit processes or micro-fulfillment zoning, they accelerate local entrepreneurship and the creation of good jobs.

Competition is another factor. As a local operator proves a delivery model, new entrants may appear. Competition can lower prices and improve service but may compress margins. Healthy competition encourages efficiency and innovation. For example, operators may adopt shared warehousing, dynamic routing software, or coordinated delivery windows to improve utilization. Local partnerships, such as shared pickup points or cooperative marketing, can help small carriers maintain profitable operations while offering consumers better value.

The presence of a dependable local delivery network also influences business formation. Entrepreneurs planning food delivery, artisan goods, or subscription services evaluate logistics costs carefully. Knowing there is an affordable local carrier reduces the entry barrier for these ventures. The availability of reliable last-mile logistics can transform a side project into a viable small business. Over time, clusters of micro-businesses supported by local delivery form a vibrant secondary economy.

Finally, the human dimension is central. Drivers who invest in their routes build relationships with customers and merchants. Trust leads to predictable work. Drivers often know the best times for pickups, the quickest alleyways, and the preferences of recurring customers. Those knowledge assets reduce friction and add intangible value that national carriers often cannot match. When drivers reinvest earnings into local amenities—housing, education, or community events—they deepen the social fabric that sustains long-term economic growth.

The impact of one delivery driver is amplified when viewed as a node in a wider urban network. Small margins per delivery compound into livelihood, local employment, and business resilience. Reinvested profits create capacity for expansion, which in turn stimulates demand for local services and supplies. Infrastructure, regulation, and competition shape the sustainability of that growth. In many cities, the collection of small operators forms the backbone of last-mile logistics, keeping commerce flowing and communities connected.

For readers seeking broader industry context, local patterns reflect national trends in employment and logistics demand. Data on employment projections and occupational shifts can help local carriers plan hiring and investments. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics maintains projections that clarify which occupations and industries are expected to grow, offering useful reference points for strategic decisions: https://www.bls.gov/emp/epchart001.htm

Local delivery is more than a route on a map. It is a conduit for economic activity, a generator of jobs, and a catalyst for entrepreneurship. With modest capital and disciplined operations, a single truck driver can set off a chain of economic events that benefit merchants, workers, and neighborhoods alike. The scale of that benefit depends on choices about reinvestment, service quality, and collaboration with other local actors. When those choices align with community needs, a small delivery business becomes an engine for city-level economic resilience and growth.

For additional reading on how industry patterns influence small carriers, see analysis of evolving market conditions in economic trucking trends: economic trucking trends.

On the Clock in the City: Break-Even, Logistics, and the Life of a Solo Delivery Driver

Sunlight spills over the southern city and casts long shadows across busy avenues where a single truck and a lone driver move more than metal and tires; they move the rhythm of local commerce. He lines up deliveries like a chess player, each stop a small gain and a potential risk, each mile measured not just in gas but in time, attention, and a plan that must stay ahead of chance. This is not a corporate fleet with a war room and a payroll department. It is a hand-built venture, born from a desire to own the schedule rather than endure it, to shape service with a direct connection to customers, and to prove that a driver can be both entrepreneur and front-line worker in the same breath. The city becomes his market and his classroom. The initial pull of independence sits beside a cold ledger of costs and a sober arithmetic about what it will take to turn effort into profit. In this light, the numbers that many treat as abstract become the weather by which the voyage is navigated.

Startup costs painted the horizon with a fixed barrier. The driver invested 2,500 dollars before the first delivery left the curb. Some of that sum bought the truck, some bought insurance and permits, and some bought a small reserve of fuel to get through the opening days. Once the vehicle was in motion, expenses did not disappear; they shifted into the variable lane. Gas, wear and tear, and routine maintenance add roughly 4 dollars per delivery. The driver set a price of 6.50 dollars per delivery, mindful that the aim is not extravagance but sustainability. To determine when the venture would stop bleeding cash and start expanding, he framed two equations. Cost equals startup plus variable costs: C equals 2500 plus 4x. Revenue equals price per delivery times the number of deliveries: R equals 6.50x. Setting R equal to C yields the break-even point: 6.50x equals 2500 plus 4x; subtract 4x, 2.50x equals 2500; divide by 2.50, x equals 1000. In plain terms, the driver must complete one thousand deliveries to reach zero profit. Every delivery beyond that becomes profit, but the margin remains slim, about 2.50 dollars per stop before other costs bite back in. This is the quiet math that governs every decision, from the morning route to the evenings’ last miles; it forces a constant negotiation with the calendar, the weather, and the fates of traffic and deadlines.

Profitability rests on more than the arithmetic. A single roll of the dice—an empty fuel tank, a sudden flat, a roadwork detour—can erase hours and dollars. The tight margin fixes a discipline: every mile must count, every stop should be reliable, and every client must be treated as a partner. The driver learns to bid carefully, to consolidate deliveries where possible, and to resist the temptation of chasing too many jobs at once. He plans for volatility in fuel prices because the per-delivery cost is a moving target when gasoline climbs or slips. He also builds a cushion for maintenance, knowing that aging components can threaten reliability just when customer trust is highest. In his city, where traffic patterns shift with school calendars, construction projects, and retail cycles, the difference between a profitable week and a loss is a handful of well-timed deliveries and a refusal to accept a fragile itinerary.

Logistics demand an almost geometric precision. Route optimization software and GPS become more than gadgets; they are the counterpoints to congestion, trying to squeeze out minutes without sacrificing safety. The driver must honor promised delivery windows while juggling late pickups, returns, or damaged items. In a dense urban fabric, one wrong turn or an unplanned detour can cascade into delays for multiple customers. The ability to forecast travel times is valuable, but the reality still hinges on the street-level world: a bus, a curbside loading zone, a truck that blocks a lane while the shopper fetches a return. Every day the plan must be resilient, capable of bending when the environment refuses to co-operate. The driver understands that his success depends not only on speed but on reliability, on meeting expectations even when there is little room for error. That reliability translates into trust he can leverage when a small business needs a late-evening delivery or an urgent restock before a weekend rush.

Physically the life is demanding. Long hours on the road demand stamina and vigilance, while the mental load—constant navigation, customer communication, and the discipline to stay within a budget—keeps pace with the miles. The body learns to adapt to irregular hours, but fatigue still arrives, sometimes masked as impatience in the face of a late delivery or a misrouted route. The concern is not only safety on the road but integrity off it: keeping the vehicle well maintained, tracking every shipment, and balancing the calendar with family and personal time. The solo driver is part navigator, part mechanic, part accountant, and part customer service representative, without a dedicated support team. This convergence is a crucible that tests stamina, judgment, and resilience. Yet many such drivers tell a similar story: independence offers a sense of control, a way to serve the local economy, and a personal brand built on punctuality and care.

Administratively the burden is real. Each delivery generates a trail of invoices, receipts, and notes that must be reconciled for taxes, insurance, and cash flow. The lack of a back-office team means the driver files and folders live in a glove compartment of memory and on digital devices that can fail. The risk is not only mismanagement but missed opportunities—a client who wants a weekly schedule but receives irregular service because a file never updated a billing account. The discipline needed to sustain such a business grows from daily routines: checking fuel efficiency, logging every mile, recording customer feedback, and maintaining records for seasonal tax credits or subsidies. In a sense the city becomes a testbed for the entrepreneur who must learn to wear many hats without losing sight of the core mission: provide dependable, courteous, and timely delivery that earns trust.

Despite the constraints, the work carries meaning beyond dollars and cents. A driver who can assemble a dependable client list earns not just revenue but credibility in an ecosystem that values speed, accuracy, and accountability. The city is both battlefield and classroom; the street network exposes opportunities while it also unveils the penalties of instability. A practical path to growth lies in tightening margins through smarter pricing, value-added services, and a careful balance of risk. This might mean negotiating longer-term contracts with steady clients, identifying backhaul opportunities to reduce empty miles, or offering specialized handling for certain kinds of packages that reward consistency. It means investing in the habits that produce reliability: meticulous record-keeping, routine maintenance, and a customer-facing presence that projects reliability. It also means acknowledging larger trends in the industry that shape what is possible: the relationship between costs, demand, and regulatory frameworks, and the way technology reshapes route planning and vehicle efficiency. For readers who track the industry, this is reflected in discussions of evolving economic patterns and policy developments that affect small operators and private fleets alike. The patterns do not erase the challenge; they illuminate it, offering context that helps an independent driver decide which bets to place and where to focus effort.

And there is a steady heartbeat that keeps the enterprise tethered to the community. The driver moves through a city that depends on his punctuality as surely as it depends on the goods he carries. Small businesses lean on him for reliability; neighbors notice when the truck arrives on schedule and when it does not. He learns to navigate the ebbs and flows of demand—holiday peaks, late-week restocks, and the quiet stretches when orders slow—and to adapt the cadence of work to the city’s mood. The daily discipline expands beyond the truck and into a small business mindset: the customer is not just a recipient of a service but a stakeholder whose continued support creates the opportunity to reinvest in the fleet, the route network, and the personal competencies that keep him competitive. There is a certain pragmatism here—do not pretend the venture will never face a breakdown or an unexpected expense; instead, accept that risk and design operating habits to absorb it. In this sense the city teaches the driver how to harness modest margins through consistency, trust, and an unyielding commitment to service that matches the pace of urban life.

For a broader understanding of how these dynamics fit into larger industry patterns, readers may explore the macro-level shifts shaping trucking economics, labor markets, and fleet strategies over time. These patterns provide context for the decisions of a one-person operation who must balance cash flow against street-level realities, and who must decide which opportunities to pursue when the road ahead is uncertain. The topic is not merely arithmetic; it is a lens on what it takes to sustain a business that is intimately tied to a city’s daily heartbeat. As the road remains the driver’s classroom, the lessons accumulate not only in the calculator but in the ever-changing choreography of traffic, deliveries, and trust. For those who follow these trends closely, the takeaway is clear: the path to growth for a solo operator lies as much in disciplined execution as in bold adaptation to the evolving economic and logistical landscape of the modern city. For a broader view of break-even analysis, see this external resource: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/breakevenanalysis.asp

Final thoughts

The role of a truck driver in a city delivery service extends far beyond simple transportation. Their operations define local economic activity and enhance the efficiency of countless businesses. By understanding the financial complexities, operational costs, and the profound economic implications of their work, stakeholders across various industries can better appreciate the value these drivers provide. As urban centers continue to grow and prioritize swift deliveries, embracing the multifaceted role of truck drivers will be vital to a thriving economy.