In today’s interconnected world, the need for efficient transportation and logistics solutions is more critical than ever. Freight forwarding companies serve as the backbone of international trade, expertly coordinating the movement of goods across borders. Businesses from manufacturing and distribution to retail and e-commerce rely heavily on these intermediaries to not only navigate the complexities of global shipping but also to ensure a seamless delivery experience. This article delves into the multifaceted roles that freight forwarding companies play, particularly focusing on their transportation arrangement capabilities, including trucking services. Each chapter unpacks a vital component of freight forwarding, illustrating how these companies facilitate logistics through multimodal solutions, manage documentation and compliance, ensure customs clearance, and provide warehousing and distribution services, all of which are essential for today’s businesses.

Coordinating the Journey: How Freight Forwarders Orchestrate Transportation and Trucking from Door to Door

A freight forwarding company acts as an intermediary between shippers and a network of transportation providers, translating a vendor’s needs into a concrete, executable plan. The process begins with a careful assessment of the shipment’s characteristics—dimensions, weight, hazardous materials status, timing, origin and destination constraints, and regulatory considerations. From there, the forwarder engines a transportation plan that often spans multiple modes. For many shipments, trucking is the first and last mile of that plan, serving as the crucial link that connects the source with the rest of the logistics tapestry. Trucks may haul goods from a factory floor to a nearby port or rail yard, then hand off to ocean or rail carriers for long-haul movement, and finally return to the road for last-mile delivery to the customer’s doorstep. This practical structure—truck, ship or rail, then truck again—represents the essence of multimodal logistics: the optimal combination of speed, cost, and reliability achieved by connecting modes through a single, coherent plan.

In this framework, trucking services are not a single service line but a suite of capabilities that forwarders knit together to meet diverse needs. Domestic trucking handles the movement within a country, often under tight time windows and strict regulatory regimes. Cross-border trucking, by contrast, introduces a layer of complexity with customs documentation, permits, and border coordination. The forwarder’s role here extends beyond route planning to include regulatory navigation, broker coordination, and risk management to minimize delays. The objective is door-to-door service—where the shipment is picked up at the supplier’s premises and delivered to the buyer’s facility or to a designated address—without the shipper needing to engage with each hand-off point directly. When the journey requires multiple legs, the forwarder coordinates handoffs so that the transfer from one carrier to another is synchronized, minimizing dwell time and reducing the chance of misrouting or damage.

To achieve this level of coordination, freight forwarders build and maintain a trusted network of carriers—trucking firms, rail operators, airlines, and shipping lines. The strength of this network lies in quality, reliability, and a shared commitment to service standards. Carriers may be regionally specialized or globally oriented, but the forwarder’s job is to match the shipment to the right partner at the right time. This allocation process includes negotiating rates, selecting service levels, and ensuring that each carrier agrees to pre-defined performance criteria. The forwarder also takes on the responsibility of service level commitments, expected transit times, and contingency plans in case of weather disruptions, port congestion, or regulatory holdups. The result is a transportation plan that fits the shipper’s priorities—whether those priorities emphasize speed, cost efficiency, or predictability—and adapts when those priorities shift.

The role of trucking within this larger frame is particularly pronounced in door-to-door logistics. In such arrangements, the forwarder assumes end-to-end accountability for pickup, transit, customs clearance where applicable, and final delivery. This accountability is what differentiates professional forwarding from a simple space-booking exercise. It requires not only access to carriers but also robust systems for routing optimization, real-time location tracking, and dynamic re-planning. Modern platforms enable the forwarder to see where a vehicle is at any given moment, estimate ETA adjustments, and communicate changes to shippers and consignees with timely, actionable information. For the shipper, this visibility reduces uncertainty and supports better planning on the customer side as well.

A key capability in trucking-enabled forwarding is the strategic use of drayage and feeder services. Drayage refers to short-haul movements, typically within a port or metropolitan area, that connect the port, warehouse, and final distribution center. Feeder trucking plays a similar role at a larger scale, transporting goods between inland terminals and regional hubs to feed a broader network. By combining these localized movements with longer-haul shipping by sea, air, or rail, forwarders can optimize network capacity, reduce dwell times, and unlock efficiencies that would be difficult for a shipper to achieve alone. This is especially valuable in regions where rail infrastructure is limited or where time-sensitive shipments demand rapid handoffs between modes.

The integration of trucking with other modes is not merely about moving goods faster; it is about delivering reliability and predictability in an inherently uncertain world. Weather, traffic, port congestion, customs checks, and regulatory changes all can disrupt a plan. Forwarders mitigate these risks through a combination of proactive planning and reactive flexibility. They prepare alternative routing options, secure buffer capacity with preferred carriers, and maintain real-time monitoring so that if a leg falls behind schedule, another leg can be accelerated to preserve the overall transit time. In some cases, this might mean re-routing a shipment from a slow rail segment to a faster truck leg when time is of the essence, or coordinating a direct trucking run to bypass a bottleneck route altogether. The ability to reconfigure routes on the fly is a hallmark of a mature, technology-enabled forwarding operation.

Documentation and compliance are inseparable from the actual transport activity. The trucking leg, as with every other leg of the journey, is anchored by proper paperwork: bills of lading, commercial invoices, packing lists, and any required certificates or permits. For cross-border shipments, this documentation must satisfy both the country of origin and the destination’s regulatory regime, and often must be harmonized with customs declarations and trade compliance requirements. The forwarder frequently works with licensed customs brokers to ensure that duties, taxes, and formalities are correctly handled and that shipments clear borders with minimal delay. In practice, the forwarder’s document management system becomes a centralized cockpit where all the necessary forms—whether for import, export, or transit—are generated, checked, and tracked. The emphasis is on accuracy, consistency, and timeliness, because even a small paperwork error can cascade into missed sailing windows, penalties, or storage charges at a port or terminal.

Alongside documentation and route design, warehousing and distribution services are often bundled into the forwarder’s offering. While some shipments travel directly from pickup to delivery, others benefit from storage between legs or at the destination. Warehousing enables inventory control, consolidation of multiple smaller shipments into a single, more economical load, and the staging of orders for last-mile fulfillment. Distribution capabilities ensure that goods not only reach the end of the line but do so in a way that aligns with customer requirements—throughput optimization, order batching, and synchronized deliveries that reduce facility congestion and enhance customer satisfaction. In this extended service model, trucking remains the essential last mile, bridging the final gap between a distribution center and an individual address, a scenario common in retail, manufacturing, and e-commerce ecosystems alike.

Technology underpins all of these activities. Freight forwarders rely on advanced transportation management systems (TMS), route optimization algorithms, and real-time tracking platforms to orchestrate the journey. Data feeds from carriers, weather services, traffic data, and customs systems merge into a single, actionable picture. For the customer, this translates into proactive updates, proactive risk management, and the ability to make informed trade-offs between speed and cost. The forwarder’s capability to anticipate issues and communicate them clearly can be the difference between a shipment arriving on time and a costly delay that ripples through a supply chain. The reliance on technology also enables greater collaboration with customers, who can participate in the planning process, adjust priorities, and request alternative routing if constraints change.

In specific cross-border contexts, the forwarder’s expertise becomes even more critical. They navigate not only the procedural complexities but also the cultural and regulatory nuances that shape how goods move between countries. They coordinate with border authorities to secure permits, arrange for inspections if required, and ensure that vehicles, drivers, and cargo meet local compliance requirements. The end result is a smoother passage, where trucks may traverse multiple jurisdictions with minimal friction, thanks to a well-choreographed sequence of checks, clearances, and handoffs. For shipments that require specialized attention—hazardous materials, perishable goods, or high-value items—the forwarder’s role expands to include risk mitigation strategies, insurance coordination, and contingency planning that protects both the cargo and the shipper’s operational plans.

The practical consequences of this integrated trucking capability extend beyond the immediate shipment. Shippers gain access to capacity that might be unavailable to them directly, enabling them to scale operations, expand into new markets, and respond quickly to demand fluctuations. Carriers benefit from stable volumes and clearer expectations, which in turn supports better asset utilization and planning. The forwarding model also aligns with broader industry trends toward sustainability and efficiency. By optimizing routes, reducing empty miles, and coordinating multi-leg itineraries that minimize dwell times, forwarding firms pursue lower carbon footprints and smarter use of infrastructure. Some forwarders even pilot programs that quantify carbon emissions and offer clients options to offset or reduce the environmental impact of their shipments.

In sum, a freight forwarding company does more than arrange a collection of transport legs. It designs an integrated, end-to-end journey that leverages trucking as the critical domestic and cross-border connective tissue within a multimodal framework. The forwarder’s expertise—carrier selection, lane optimization, regulatory compliance, documentation, warehousing, and real-time visibility—transforms a complex global supply chain into a manageable, predictable operation. This orchestration is not simply about moving goods from point A to point B; it is about engineering reliability and efficiency into the heart of international trade, ensuring that shipments arrive on time, intact, and within the agreed service levels. For businesses navigating the intricacies of global commerce, the freight forwarder becomes less a supplier of space and more a partner in strategic execution, turning logistical challenges into practical, repeatable outcomes.

For readers seeking a broader perspective on what freight forwarders do, including the role of brokerage and the coordination of multiple transportation modes, a widely cited overview emphasizes the same core idea: forwarders act as intermediaries who combine a range of service providers to deliver end-to-end visibility and support. More detail on the nature of a freight forwarder’s value can be found in industry resources that outline these functions and illustrate how trucking integrates with other modes to produce reliable, door-to-door service. Cross-border regulatory issues are one tangible example of the regulatory dimension forwarders manage to keep shipments moving smoothly.

External resource: https://www.chrobinson.com/en-us/what-is-a-freight-forwarder

From Doorstep to Global Gateways: The Strategic Role of Multimodal Logistics in Freight Forwarding, Including Trucking Services

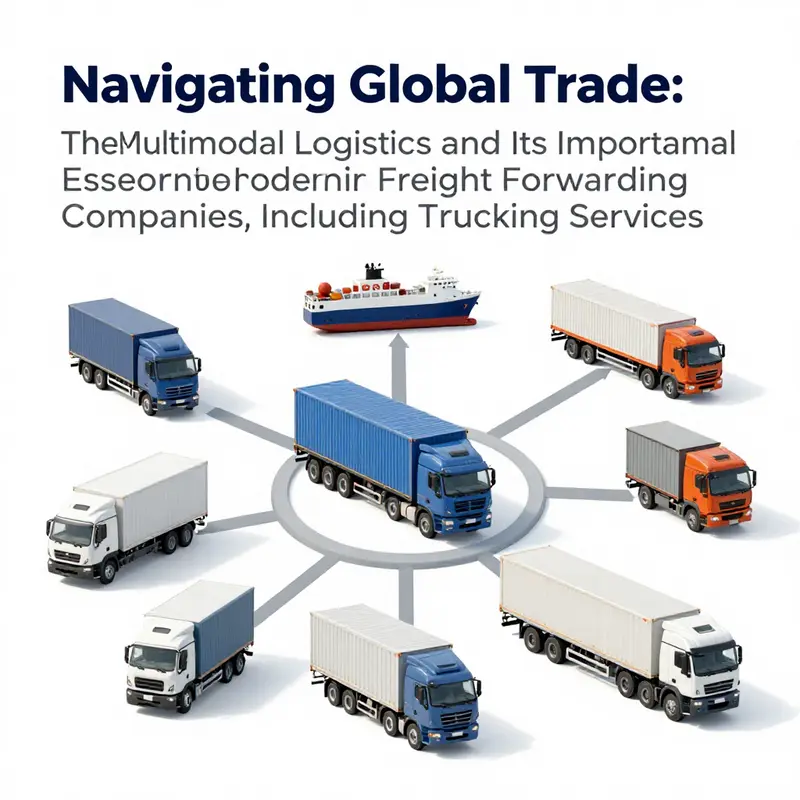

When a shipment crosses a border, it is rarely the end of a journey. For a freight forwarding company, it is the moment to translate a simple order into a carefully engineered movement that threads together multiple modes of transport, disciplines, and regulatory requirements. Multimodal logistics sits at the heart of this orchestration, turning what could be a logistical maze into a single, coherent voyage that begins with a pickup and ends with a delivered parcel. In practice, the trucking leg—whether it kicks off the journey, handles drayage between ports and warehouses, or finishes with a precise last mile—acts as both the first touch and the final mile of a larger supply chain. To understand its importance, it helps to think of multimodal logistics not as a collection of tricks but as a philosophy: design the route to leverage the strengths of each mode while maintaining a seamless, transparent experience for the customer.

A freight forwarder does not typically own the trucks, ships, or aircraft that move goods. Instead, they curate a network of carriers, ports, warehouses, and service providers, then design the route, time plan, and documentation that bind these moving parts into a single, accountable shipment. The trucking segment plays a pivotal role in this design because it is the most flexible and responsive mode. It can deliver goods door to door, adapt quickly to last-minute changes, and serve as the bridge that connects a producer’s dock to a port, a warehouse, or a distribution center. Yet the value of trucking within the multimodal mix is maximized only when it is harmonized with rail, sea, and air legs. A forwarder’s skill lies in understanding where trucking adds speed and reliability, where rail or sea optimizes cost over distance, and how to schedule transfers with minimal handling and risk.

At the core of multimodal logistics is the idea of standardized cargo units and smooth handoffs. Standard containers and unified documentation enable different transport modes to interoperate with fewer delays. This standardization reduces the need for multiple, duplicative customs checks and minimizes the risk of misrouting during transfers. The forwarder, therefore, invests in visibility platforms and data governance that make every leg of the journey legible to the shipper and the consignee. Real-time tracking, ETA updates, and proactive exception management give shippers confidence that their goods are not simply moving, but moving toward a target. The efficiency gains are not only about speed; they also translate into reduced handling, lower damage risk, and more predictable transit times, all of which lower total cost of ownership for the customer.

The process begins with a deep dive into the shipment’s specifics: product characteristics, packaging, weight, dimensions, hazardous material status if any, and the required regulatory clearances. From there, the forwarder crafts a multimodal route that aligns with the customer’s priorities—whether that is the fastest possible transit, the lowest total landed cost, or the most robust contingency plan for disruption. If the origin is inland, trucking initiates the voyage, moving goods to a rail terminal or a port facility where the next leg will begin. If the shipment originates at the coast, trucking may be the final mile from the warehouse to the consignee, or it may drayage the cargo from the ship’s berth to a nearby consolidation center. In either scenario, every leg is planned with a mind to reducing non-value-added handling and enhancing control over the schedule.

A distinctive advantage of the multimodal approach is the ability to design routes that exploit the relative efficiencies of each mode. Rail offers high-volume, long-haul efficiency with lower per-ton costs over land, making it ideal for moving large quantities across continents. Sea transport remains the backbone of international trade, delivering scale for imports and exports with cost effective performance that is hard to match by air or road alone. Air freight provides speed for time-sensitive goods, while trucking delivers nimble, door-to-door execution for the critical last mile and for movements that require rapid deployment or flexible rerouting. The forwarder’s job is to assemble these pieces into a cohesive plan where the transfer points are predictable, the documentation is synchronized, and the risk of delays is minimized.

This integration is not simply a matter of routing. It also hinges on the careful management of documentation and compliance. Bills of lading, commercial invoices, packing lists, and certificates of origin are more than paperwork; they are the formal threads that hold the entire chain together. Customs clearance and brokerage further tighten the knot, ensuring that goods move through borders smoothly and without penalties. A competent forwarder coordinates with licensed customs brokers, pre-clears shipments when possible, and uses standardized documents to accelerate processing at entry and exit points. In a world where delays at the border can erase any advantage gained by a faster mode, this compliance discipline becomes a differentiator. It also reinforces the perception of a one-stop solution, where the customer interacts with a single party charged with end-to-end responsibility rather than a loose assembly of providers.

Warehousing and distribution are often integrated into multimodal offerings because storage can stabilize the flow of goods through a complex route. Inventory management, order fulfillment, and last-mile delivery columns can sit alongside the core movement plan, enabling a more resilient supply chain. The value is especially evident in seasonal peaks or sudden demand shifts when the ability to stage goods near destination markets shortens lead times and cushions against capacity crunches in one or more modes. Forwarders increasingly provide cross-docking, Consolidation, and pick-and-pack services as part of a seamless logistics solution, reducing time-to-market for the shipper and giving the customer more predictable service levels.

A reliable multimodal plan depends on continuous visibility. Tracking technologies, integrated data feeds, and standard communication protocols keep the entire network in view. Instead of waiting for periodic updates from individual carriers, shippers receive a live picture of where the cargo is, what to expect next, and how to respond to exceptions. This transparency is crucial when a shipment runs afoul of a regulatory hold, a port congestion situation, or an unforeseen weather event. The forwarder’s ability to adapt in near real time—re-routing, switching modes, or mobilizing alternative carriers—can be the difference between a late delivery and a satisfied customer.

Beyond speed and cost, multimodal logistics contributes to resilience and sustainability. By distributing the workload across multiple modes, freight forwarders can avoid overreliance on a single choke point. A well-conceived multimodal plan can weather port congestion, truck bottlenecks, or rail service disruptions by shifting lanes within the ecosystem without letting the shipment derail entirely. On the environmental front, efficient intermodal networks often yield lower emissions than a purely road-based solution. When freight moves by ship or rail for the long-haul sections, fuel burn concentrates where it is most efficient, and the remaining road legs are typically shorter and more economical. Industry analyses suggest substantial CO2 reductions are achievable through modal shifts, particularly on long-haul journeys that would otherwise ride exclusively on trucks.

The strategic value of multimodal logistics is also reflected in the business model that freight forwarders increasingly pursue. The traditional broker role—finding a carrier for a given leg—gives way to an integrated service platform that emphasizes end-to-end responsibility and streamlined administration. The “one-stop shop” model is not merely a marketing phrase. It translates into a single contract, a single point of contact, and a unified documentation package that covers every leg of the journey. For shippers, this reduces the cognitive and administrative load, converting a potentially fragmented experience into a single, coherent project with clear performance metrics and accountable timelines. The simplification pays dividends in planning accuracy and customer satisfaction, especially when dealing with complex trade lanes, regulatory requirements, or time-critical shipments.

Innovations in digitalization further accelerate the effectiveness of multimodal logistics. Concepts such as standardized digital documents and integrated shipment portals allow for smoother handoffs between trucking, rail, maritime, and air legs. In some markets, industry-wide efforts toward interoperability have begun to bear fruit, with systems designed to minimize redundant data entry and expedite customs clearance. The result is not a sterile, computer-driven process but a more human, decision-ready flow where the forwarder’s expertise guides technology to anticipate issues, optimize routing, and safeguard against delays. In spaces where regulatory regimes differ markedly from one country to the next, this blend of expertise and digital capability helps ensure that multimodal plans not only move goods efficiently but also remain compliant and auditable.

The global trend toward more resilient, cost-aware, and sustainable supply chains underscores why multimodal logistics is no longer a luxury but a competitive necessity for freight forwarders with integrated trucking capabilities. When shipments can be designed with a full awareness of port throughput, rail capacity, trucking availability, and last-mile demand, shippers gain reliability and predictability even in volatile markets. The model externalizes value in the form of reduced handling, tighter synchronization across modes, and stronger partnerships with carriers and service providers who share a commitment to on-time performance. For businesses navigating cross-border corridors, where regulatory complexity and variability in transit times are the rule rather than the exception, the multimodal approach provides a disciplined framework for risk management and service continuity. The emphasis shifts from merely moving cargo to managing a synchronized ecosystem that keeps shipments flowing smoothly, even when one channel encounters a disruption.

This emphasis on end-to-end visibility and cohesive policy is precisely why many forwarders strive to present a unified front. The synergy of trucking within a multimodal plan creates a robust platform for growth. It enables companies to offer more predictable quoting, better delivery windows, and stronger contingency options. It also supports the development of long-term client relationships built on the credibility of consistent performance rather than the occasional brilliance of a single leg. In an industry where customers increasingly expect transparent pricing, reliable transit, and ethical, compliant operations, multimodal logistics provides a durable competitive edge. It aligns the forwarder’s capabilities with the shipper’s priorities—speed for urgent shipments, cost discipline for high-volume flows, and sustainability for organizations pursuing greener supply chains.

The human element remains central. No amount of digital sophistication can substitute for the professional judgment of planners who understand local conditions, regulatory nuances, and the realities of equipment availability. The most successful multimodal programs blend data-driven optimization with a seasoned sense of practical risk management. They recognize when to lean on trucking for the last-mile flexibility that city streets demand and when to switch to rail or shipping to unlock scale and efficiency on long-haul legs. The result is a streamlined, end-to-end solution that feels, to the shipper, almost single-threaded—even as it is truly a tapestry of coordinated, cross-functional activity. And because the operational backbone is shared across all legs—from pickup to gateway to final mile—the shipper experiences fewer surprises and greater confidence in meeting delivery commitments.

For readers seeking depth beyond the mechanics, consider the broader context in which multimodal logistics is evolving. The industry’s push toward standardized, document-centric processes, sometimes called a One-Document or One-Contract System in certain markets, illustrates how digitalization can compress administrative timelines and accelerate transit while preserving compliance. The trend toward greater intermodal integration is not merely a convenience; it is a strategic response to supply chain fragility, rising freight costs, and the growing importance of sustainability. As global trade patterns shift and new corridors emerge, forwarders who master multimodal design—who can blend trucking with rail, maritime, and air in a single, coherent plan—will be best positioned to capture market share and earn lasting client trust. The human and technological elements together create a resilient architecture capable of adapting to disruptions, from border processing delays to capacity shortages, and still deliver predictable outcomes for customers.

For practitioners and scholars alike, the practical takeaway is clear: successful freight forwarding hinges less on any single mode and more on the orchestration of multiple modes into a single, customer-centric journey. The trucking component is essential, but its value multiplies when it is nested within a deliberate multimodal strategy that optimizes route, mode, and timing while upholding compliance, visibility, and sustainability. In this light, multimodal logistics is not just a technique; it is the operating system of modern freight forwarding, the framework that makes door-to-door service possible across a global logistics landscape that remains as dynamic as the markets it serves. And as the trade environment continues to evolve—with new regulatory regimes, capacity cycles, and environmental expectations—forwarders equipped with multimodal expertise and a robust trucking backbone will be uniquely positioned to deliver the reliable, efficient, and responsible service that modern shippers demand.

To delve further into the sustainability and intermodal efficiency narrative, see external research on multimodal transport and sustainability: https://www.iru.org/intermodal-transport-and-sustainability.

For readers seeking a practical connection to ongoing industry conversations, this chapter also nods to the cross-border realities that shape routing choices and compliance considerations. The topic of cross-border regulatory issues is increasingly central to every multimodal plan, and it is worth exploring how policy developments influence scheduling, documentation, and carrier partnerships. You can explore a focused discussion on these regulatory realities here: cross-border regulatory issues.

Documentation, Compliance, and Trucking: The Pillars of Freight Forwarding

A freight forwarding company acts as the conductor of a complex logistics orchestra, moving goods between continents, across borders, and toward the end customer. The forwarder does not own the trucks, ships, or rails that carry cargo, but coordinates a global network of carriers, freight exchanges, and service partners to deliver on time and on specification. The inseparable trio of documentation, compliance, and trucking is what makes the handoffs reliable, the tariffs predictable, and the delivery window achievable. The path a shipment takes is shaped by a disciplined choreography that begins with accurate paperwork and ends with verifiable performance.

Open, precise documentation is the first gate a shipment must pass through. Every document functions like a passport, carrying essential information about goods, value, origin, destination, and the parties responsible at each leg. The commercial invoice communicates price and terms; the packing list clarifies how and where items are packed; the bill of lading serves as the contract of carriage and, in many systems, as receipt of goods. A certificate of origin may be required to secure preferential tariffs or to prove compliance with trade agreements; export declarations and import permits show that goods move under the sanctioned rules of the exporting and receiving nations. When any piece of this tapestry is incomplete or misaligned, shipments risk delays, penalties, or seizure. In practice, it is not enough to exist; the data must line up across documents, reflect correct harmonized system codes, quantities, weights, and classifications.

Compliance goes beyond paperwork. Forwarders steward a broader set of rules that govern border crossing and cross-border movement. International regulations touch details from wood packaging treated to ISPM 15 to sanctions, export controls, and destination-country documentation demands. The forwarder must verify that every actor in the chain conforms to those rules. This verification safeguards the shipment and the integrity of the supply chain. The complexity grows when shipments traverse multiple jurisdictions, where even a small item can trigger a filing or certification. The forwarder’s knowledge shifts from fastest routes to legally sound, feasible, and traceable routes, and the best operators anticipate and prevent issues by building compliance into every step.

Truck transportation, domestic or cross-border, is the visible hinge between the logistics web and the end customer. The trucking component is not a standalone service but an integral part of the end-to-end plan. Compliance in trucking includes licensing, hours-of-service, maintenance, and safety standards; hazmat or specialized cargo require explicit handling guidelines. The forwarder vets carriers for insurance, safety, and compliance histories, aligning their capabilities with the shipment’s profile and delivery window. The trucking layer is the face of the forwarder’s service: cargo reaches its destination under the rules that govern safety and legality along the way. Missteps here can breach contracts, violate regulations, or cascade into downstream costs for a client’s supply chain.

The forwarder’s approach blends standardized templates, scalable checklists, and digital workflows to synchronize information across systems. Electronic data interchange (EDI) reduces data entry errors and speeds clearance, while real-time visibility transforms guesswork into auditable, predictable journeys. When issues arise, the forwarder responds with proactive communication, corrective amendments to classifications, and collaboration with customs brokers to resolve problems before they become delays. The result is consistency: accurate data, compliant classifications, and timely documentation, regardless of route shifts or market conditions.

In practice, success rests on people, processes, and relationships. Teams maintain regulatory knowledge across regions, renew licenses and certifications, and coordinate with customs brokers to ensure smooth entry. For cross-border operations, harmonizing differences between sides of a border is a core capability, translating regulatory complexity into dependable performance. The value of a freight forwarder lies in disciplined governance of information, documents, and legal compliance that makes movement across borders reliable and predictable. The trucking component, woven with documentation and compliance, becomes the connection between paper trails and pavement, enabling a consistent service that customers can count on.

For readers seeking deeper insight, industry guidance and educational resources reinforce practical steps for maintaining accuracy and regulatory alignment throughout the logistics process. The overall message is clear: meticulous documentation and proactive compliance reduce risk, speed movement, and protect timelines from the first mile to final delivery.

Borders, Paperwork, and the Last Mile: How Customs Clearance and Trucking Shape Modern Freight Forwarding

A freight forwarding company acts as the conductor of a complex orchestra, coordinating a shipment’s journey from origin to destination while ensuring the music stays in harmony across borders. It is not about owning fleets or vessels; it is about expertise, networks, and the seamless stitching together of diverse transport modes. Within this orchestration, customs clearance and brokerage sit at the core, serving as the bridge between the sender’s intent and the legal reality of moving goods through foreign soil. The forwarder’s value emerges from turning what could be a labyrinth of forms, rules, and fees into a predictable path to delivery. They manage the critical dialogue with customs authorities, brokers, and carriers, translating commerce into compliant, timely movement. This is especially vital when trucking services enter the picture, because land leg provides both the final touch and the middle mile between ports, warehouses, and customer doorsteps. In many supply chains, trucking is not an afterthought but a pivotal link that pulls the entire itinerary from paper into practice. The forwarder’s role, then, encompasses more than logistics; it is risk management, strategic planning, and customer advocacy, all folded into a single point of accountability.

Documentation and compliance weave the first layer of this work. The paperwork begins long before a shipment arrives at the border. Bills of lading, commercial invoices, packing lists, and certificates of origin are not mere formalities; they are the passports that enable movement. Each document carries data that determines how goods are classified and taxed, whether licenses are required, and what regulatory restrictions may apply. Accuracy matters because a small misclassification or an overlooked restriction can trigger audits, penalties, or costly delays. Freight forwarders invest in robust classification processes that align goods with the correct tariff codes and the corresponding duties and taxes. They coordinate with licensed brokers to ensure that customs declarations reflect the true nature of the goods, their value, and their country of origin. This collaboration reduces the risk of compliance gaps and creates a smoother passage through inspection queues. The result is more than compliance; it is operational continuity, which preserves cash flow and confidence for businesses that rely on predictable timelines to meet customer demand.

When trucking enters the equation, the forwarder’s scope widens into end-to-end execution. The multimodal logic that governs freight today is built on the premise that land transport complements sea and air legs, often in a sequence that minimizes transit time while controlling costs. In practice, this means designing routes that may begin with a port-to-warehouse leg, pass through cross-border drayage, and culminate in door-to-door delivery. A typical scenario might involve coordinated ocean freight from a manufacturing hub to a major inland gateway, followed by truck transportation to a regional distribution center. The trucking component is not merely a final mile service; it is an integral segment that shapes transit times, risk exposure, and visibility. By managing trucking directly or through a trusted network, the forwarder reduces handoffs, which in turn lowers the chance of miscommunication, misrouting, or lost paperwork. The result is a tighter control loop: the same organization that orchestrates the ocean schedule also calibrates the inland moves, ensuring speed aligns with compliance and capacity with demand.

This integrated approach unlocks substantial value for goods moving through dense logistics hubs. Consider a scenario where components sourced in one region converge with finished products from another, requiring rapid, synchronized movement to a shared destination. The forwarder crafts a multimodal solution that aligns air, sea, rail, and trucking into a single, coherent itinerary. The benefit is not only speed but predictability in cost and timing. When trucking is embedded in the service, it offers a direct link to the last mile, which is often where margins and customer satisfaction hinge. In hubs that teem with activity—ports, industrial parks, rail yards—having a single partner that coordinates the flow simplifies governance and performance measurement. Real-time tracking becomes more than a feature; it is a central promise of visibility, providing suppliers and recipients the assurance that cargo is on a known path and on schedule. This clarity supports tighter inventory management, reduces safety stock, and accelerates response times to unforeseen disruptions.

To stay competitive, forwarders cultivate and maintain a robust regulatory posture. The modern logistics landscape features heightened scrutiny and evolving trade rules. A forwarder’s credibility rests on robust customs brokerage capabilities and a well-supported trucking infrastructure. The combination enables swift clearance after the goods reach the border and reliable, compliant inland transport to the destination. An effective operator maintains a broad, yet precise, understanding of Incoterms, which define who bears costs and risks at each stage of the journey. Flexible Incoterms reduce friction when routes shift or when new obligations arise during transit. Another crucial asset is the Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) status that many reputable forwarders pursue. AEO status signals trusted compliance to customs authorities across numerous jurisdictions and can expedite clearance and reduce scrutiny in routine assessments. These strategic assets translate into tangible outcomes: fewer delays, lower penalties, and steadier throughput, even when regulatory complexity intensifies.

Beyond compliance, the integrated model supports broader supply chain resilience. The freight forwarder acts as a buffer against the unknowns that plague international trade, from regulatory changes to port congestion. When lead times tighten or a disruption threatens the continuity of a shipment, the forwarder can reroute, re-sequence, or substitute modes with minimal disruption to the customer. The trucking component offers a vital degree of agility, enabling rapid on-ramp and off-ramp adjustments at key nodes. Such adaptability is increasingly essential as global networks diversify suppliers and markets. It is this capacity for agile, informed decision-making that turns a set of regulatory steps into a smooth operational rhythm. The forwarder’s brokerage role remains essential here, because it ensures that any course correction preserves compliance while minimizing new liabilities. The interplay of customs expertise, trucking dynamics, and live shipment data creates a proactive rather than reactive supply chain posture.

The human element underpins this entire construct. Compliance specialists, licensed brokers, and logistics coordinators work in concert with drivers, dispatchers, and warehouse teams. The people side is what translates policy and data into practical action. For shippers, this means access to a single point of contact who understands evolving requirements, monitors the pace of clearance, and coordinates the handoff between border control and final delivery. It also means a partner capable of interpreting regulatory nuance for unique products, markets, or risk profiles. The most effective forwarders cultivate deep local knowledge in multiple jurisdictions while maintaining a global framework that aligns with international best practices. In a world where data flows are as important as physical movement, the blend of local execution and global standards becomes a compass for maintaining service levels across continents and seasons.

The embedded trucking capability also reshapes how shippers think about cost and service quality. When a forwarder manages the last mile as part of the same contract, there is a direct line of accountability from the origin to the door. This encourages optimization of packaging, labeling, and load configuration to reduce rework and delays at the destination. It also sharpens the accuracy of delivery estimates and improves the reliability of commitments to customers. In practice, this integration translates into shorter cycle times, better inventory turns, and a stronger value proposition for businesses that rely on international sourcing and distribution. The chain of custody is clearer, the escalations are faster, and the ability to forecast capacity aligns with demand signals, creating a smoother, more predictable operating environment for everyone involved.

For organizations seeking to select a freight forwarding partner, the choice hinges on more than price or speed. It hinges on the capacity to blend customs brokerage with a robust trucking network into a single, accountable workflow. A forwarder with strong cross-border execution understands not only how goods move but why they move that way. They interpret trade regulations, anticipate possible changes, and translate strategic objectives into a practical, compliant route. They also preserve the integrity of the supply chain by ensuring that every handoff—whether from border to truck, or from truck to warehouse—is documented, traceable, and auditable. In a field where a minor delay can ripple into missed deadlines and dissatisfied customers, that reliability becomes a competitive advantage. To appreciate the full value of such a provider, imagine the alternative: a fragmented set of service providers, each owning a piece of the puzzle but lacking the cohesion to align schedules, customs entry, and final delivery. The difference in risk exposure, cycle time, and cost is substantial.

If you are navigating cross-border complexity, it helps to think of the forwarding partner as a governance layer for your shipment. They translate policy into practice, convert risk into process, and render the border a navigable crossing instead of a hurdle. The last-mile trucking component anchors the whole operation in the real world, converting an international journey into a tangible, trackable delivery experience. This is the core reason why customs clearance and brokerage, when embedded within a trucking-enabled freight forwarding model, matter so much to modern trade. It is not merely about moving goods; it is about turning a potentially fractious international process into a reliable, streamlined, end-to-end service that supports growth, resilience, and operational continuity. For businesses with global ambitions, such a partner does not just facilitate movement; they enable scale by removing friction from the supply chain, one shipment at a time.

Internal link reference: For deeper context on regulatory considerations that can affect cross-border operations, see the discussion on cross-border regulatory issues. cross-border regulatory issues.

External resource for further reading: https://www.dhl.com/global-en/home/services/forwarding/customs-clearance.html

null

null

Final thoughts

In summary, freight forwarding companies play a pivotal role in the global logistics landscape, offering essential services that transcend mere transportation. Their expertise in arranging multimodal transport, managing documentation, ensuring compliance, facilitating customs clearance, and providing warehousing solutions is invaluable for businesses of all sizes. By harnessing these capabilities, organizations can enhance their shipping efficiency and focus on their core operations. Understanding and utilizing the comprehensive services offered by freight forwarders—including crucial trucking options—can significantly improve your supply chain performance and customer satisfaction.