The service brake pedal in trucks is critical for safe and efficient vehicle operation, impacting various industries from construction to transportation. This article examines the service brake pedal in detail, uncovering its functionality, significance in safety, and maintenance protocols. Each chapter delves into the nuances of the service brake system, providing a comprehensive understanding of how this essential component aids in controlling heavy vehicles and promoting operational safety.

From Footstroke to Stopping Power: A Comprehensive Reading of the Brake Pedal as the Truck’s Service Brake

The brake pedal is the primary human interface to the service brake, the system that converts driver intention into predictable deceleration in daily operation. When a boot presses the pedal, a carefully choreographed sequence begins that translates foot pressure into controlled braking torque at the wheels. This is not a single switch but the first link in a chain that connects human feedback to physics, hydraulics or pneumatics, and wheel friction. The service brake remains distinct from the parking brake or emergency braking systems; it is the workhorse that enables safe, steady deceleration during normal driving and performance braking in a crisis. Understanding the pedal requires tracing that chain from pedal travel to wheel torque, and imagining how it behaves as trucks carry heavier payloads, climb grades, or encounter slick surfaces. The pedal is a feedback-laden gateway, not a mere actuator, and it deserves examination as a device that shapes safety and confidence on the road.

The historical arc of the pedal mirrors the evolution of the braking system itself. Early trucks used direct mechanical linkages where the pedal pulled cables or rods to brake moments on all wheels. The advantage was immediacy and simplicity, but the arrangement demanded exact synchronization and was susceptible to cable stretch and misadjustment. As trucks grew heavier and more complex, designers shifted toward multi-axle control and eventually toward air-brake or hybrid systems that decouple the driver input from the wheel-end actuation in more sophisticated ways. The modern service brake is thus a network: the pedal signals a valve, the valve modulates pressure in a distributed circuit, and brake actuators at each wheel respond with friction. Across this arc, the fundamental promise remains the same: pedal input should produce a predictable, linear, proportional response in deceleration under a wide range of operating conditions.

In contemporary heavy trucks, the service brakes are predominantly air-based, often with hydraulic or electrical assistance enhancing pedal feel and response. The pedal movement triggers a brake control valve, which interprets position and force and then modulates compressed air to the brake chambers on each axle. When air pressure reaches the chambers, pistons or diaphragms move to apply the brake shoes or pads, generating friction with drums or discs and slowing the vehicle. This architecture allows the same pedal motion to produce scalable braking force across multiple axles and load conditions. The key insight is that pedal position becomes a pressure signal, which becomes mechanical action at the wheel, which then translates into kinetic energy being dissipated as heat by friction. The efficiency and reliability of this chain depend on control valves, air supply, and the quality of fittings and hoses that feed the circuit.

Beyond the basic pressurization cycle, the pedal interacts with active safety systems that shape how braking occurs in real time. Anti-lock braking systems prevent wheel lock by modulating brake pressure when wheels approach the limit of traction. Brake-force distribution optimizes how much braking effort is directed to the front versus rear axles, preserving steering and stability. Some trucks pair these controls with brake assist logic that detects emergency scenarios and amplifies braking force for shorter stopping distances. In a modern system, the driver’s foot remains the tactile anchor, while the vehicle’s electronics interpret pedal inputs into a safe, efficient braking strategy. The driver senses feedback from pedal travel, resistance, and the progressive bite of the brakes, using that feedback to modulate pressure with finesse in everyday driving and during abrupt, emergency stops.

A core theme in brake pedal operation is predictability. The driver’s goal is to feel a smooth, linear response that corresponds to the amount of foot pressure and the road conditions. When the road is slick or heavy loads are shifting, pedal travel may increase before the brakes bite; when the vehicle is on dry pavement and within weight and speed envelopes, the brake bite should feel immediate and controlled. The ideal pedal not only provides stopping power but also conveys the system’s health and capability. If pedal travel grows without a corresponding deceleration, or if braking feels grabby or uneven, it signals a mismatch in the brake control valve, air supply, or wheel-end components, and it invites timely maintenance to preserve safety margins. The pedal thus functions as both a control input and a sensor of the braking system’s health, linking human judgment with mechanical reliability.

From a fleet-management perspective, braking efficiency ties directly to safety, uptime, and cost. A well-tuned pedal and brake network help ensure predictable stopping distances across diverse loads and routes, support efficient fuel use by enabling smoother deceleration, and reduce the risk of wheel lock and brake fade on long descents. Fleets increasingly adopt data-driven maintenance practices that correlate pedal feel, brake wear, and performance metrics with service schedules and regulatory inspections. In this context, the pedal is not only a driver interface but a data point in a broader safety and maintenance culture that prioritizes proactive care over reactive fixes. Roadside or fleet-scale diagnostics now often include pedal feedback as part of a holistic braking health assessment.

Regulatory expectations frame how braking systems are designed and evaluated. The FMCSA and other authorities publish standards that describe required performance ranges for service brakes, testing procedures, and components’ reliability. As fleets and manufacturers align to these rules, the pedal’s role in ensuring consistent deceleration becomes a matter of compliance and safety. For practitioners seeking formal references, official brake regulations and guidance provide the detail behind performance requirements, testing regime, and maintenance practices that uphold public safety on the highway. The pedal thus sits at the intersection of human factors, engineering, and governance, embodying a system that must be both responsive to a driver and robust under the demands of real-world operation.

In sum, the brake pedal is more than a simple button; it is the gateway to a complex, safety-critical network that translates human intention into controlled slowing. Its design emphasizes linearity, predictability, and resilience across loads, speeds, and conditions. By understanding the pedal as the start point of a controlled sequence—from input to valve action to wheel end friction—readers can appreciate how this small device anchors the broader mission of safe, reliable trucking.

The Service Brake Pedal: Command, Feedback, and Safety in Truck Braking Systems

The service brake pedal is more than a simple interface; it is the driver’s primary means of imposing deceleration on a heavy vehicle. In the cab, the pedal remains the focal point through which human intention becomes mechanical action. When a driver presses the brake pedal, the intent to slow or stop is translated into a cascade of pressure that travels through the brake system. In traditional hydraulic setups, this pressure is transmitted through master cylinders, brake lines, and control valves to the brake calipers and wheel cylinders. In air brake configurations, the pedal movement modulates a brake control valve that routes compressed air into the brake chambers. The result is friction material pressing against rotors or drums, converting kinetic energy into heat and slowing the vehicle. Across the spectrum of heavy trucks, the service brake pedal remains the key element that connects driver decisions with the physics of stopping. The pedal’s role is so fundamental that it underpins safe operation in routine driving as well as in emergency maneuvers. Its proper use, therefore, is not merely a matter of technique but a matter of vehicle safety and fleet efficiency.

The pedal’s location is a practical detail that affects every deceleration event. In many cab layouts, the service brake pedal sits to the left of the accelerator, a position that makes it quickly reachable without shifting the foot or hand from the primary operating zone. This arrangement supports rapid, repeatable engagement, a quality drivers rely on when traffic suddenly requires braking. Within the cab, the driver’s foot typically makes a smooth arc when applying pressure, and the force applied correlates directly to the braking pressure in the hydraulic or pneumatic circuits. The better the correspondence between pedal input and brake pressure, the more predictable the deceleration profile. This relationship matters not only for comfort but for stability, especially on long descents or in conditions that demand careful speed management. A precise, proportional response reduces the chance of abrupt weight transfer or wheel lock and makes it easier for the driver to modulate speed without overusing the pedal.

The basic physics of braking are timeless, but the practical realities differ with the truck’s propulsion and braking architecture. In conventional heavy trucks, pressing the brake pedal sends a signal to a brake control valve or master cylinder that translates pedal motion into hydraulic pressure. In heavier configurations, this pressure is distributed through a network that can include multiple circuits, ensuring that if one part of the system experiences a fault, the others can still provide stopping power. The driver’s action is the trigger, but the system’s responsiveness depends on the integrity of the valves, lines, and actuating components. The force relationship—the proportionality between pedal effort and braking pressure—gives the operator the means to fine-tune speed reduction. A light touch yields gentle deceleration, ideal for maintaining traffic flow and passenger comfort. A firmer press delivers stronger friction and a shorter stopping distance, essential in an emergency. The driver learns to read the pedal’s feel, the way it resists or yields, and to translate that feedback into appropriate control inputs.

In modern braking ecosystems, the service brake pedal operates within more than just a friction-based framework. For trucks equipped with advanced electronic or electric systems, a dual function often comes into play. As the pedal is pressed, conventional friction braking may be activated alongside regenerative braking, if the vehicle’s architecture permits it. The regenerative pathway captures energy during deceleration and channels it back into the battery or energy storage system, contributing to extended range or reduced energy use in hybrid or electric trucks. The presence of regenerative braking does not replace friction braking; rather, it augments braking capability and can alter the pedal’s feel during deceleration. The pedal thus becomes a gateway to both mechanical energy conversion and energy recovery. In such systems, the vehicle still relies on ABS to prevent wheel lock and maintain steerability during hard braking. ABS modulates brake pressure at each wheel, ensuring that deceleration remains controllable and predictable even when road conditions are challenging. The driver may notice a pulsation or vibration in the pedal during aggressive stops; this is the ABS telling the driver that wheel-by-wheel modulation is active, not that something is wrong. The rider feels the system’s choreography, which is a cue to maintain steady pedal pressure rather than lift off during the stop.

The ABS is perhaps the most conspicuous safety feature connected to the service brake pedal’s operation. By comparing wheel speeds and intervening when slip is detected, ABS prevents the wheels from locking, allowing steering control while braking hard. The driver’s foot may sense intermittent pulses as the system repeatedly adjusts pressure, a signal that the vehicle is actively seeking the optimal balance between deceleration and directional control. This feedback can be disconcerting at first for some drivers, but it is a normal aspect of modern braking. The crucial point is that the pedal remains the driver’s direct link to the vehicle’s braking intentions; the ABS acts behind the scenes to realize those intentions safely. When ABS is functioning correctly, the stopping process remains smooth and regulated rather than starkly abrupt. In the most demanding conditions, this synergy between pedal input, friction braking, and anti-lock modulation helps keep the tires within their grip envelope and preserves the driver’s ability to steer toward a safe outcome.

Consider the evolving landscape of braking in electric and hybrid trucks. The service brake pedal’s command is integrated with electronic control units that coordinate both friction and regenerative pathways. The pedal’s push translates into a command that may engage a friction brake actuation while simultaneously allowing motors to operate in a regenerative regime. The precise balance depends on factors such as vehicle speed, battery state of charge, and system software. This integration can reshape the driver’s perception of braking. Instead of a purely mechanical signal, the pedal input becomes a tripwire for a multi-channel braking strategy. Yet the driver still experiences the fundamental physics of deceleration—heat generation in brake components, friction pad wear, and tire-road interaction—while energy is harvested and fed back into the vehicle’s energy system. The sense of control stems from the driver’s ability to modulate the pedal in a way that respects these competing objectives: safety, progress toward a destination, and energy efficiency.

Beyond the pressure-to-pressure translation and beyond the neat separation between hydraulic and pneumatic branches lies the look, feel, and safety sense of the pedal. The pedal feedback mechanism—whether it is a consistent resistance in the face of modest engagement or a firmer, progressive engagement as braking intensity increases—offers a tactile map for the driver during every deceleration. Pedal feedback signals that ABS is active, a necessary reminder for the driver to maintain steady pressure during an emergency stop rather than lifting off. The way the pedal responds under varying loads and tire conditions becomes part of the driver’s internal model of the vehicle’s braking behavior. That model is built up through training, experience, and a continuous awareness of how the road surface, weather, and vehicle load shape braking performance. For drivers who operate in fleets where maintenance and operation must be predictable, this intuitive control is essential. It helps to minimize abrupt stops, reduces wear on braking components, and supports safer maneuvers in congested traffic or adverse conditions.

Safety indicators on the dashboard complete the picture of the service brake pedal’s responsibilities. A red brake warning light illuminates to signal a fault in the braking system or a critically low brake fluid level. This alert is a call to action for immediate attention, because a failure in the braking system directly compromises stopping power and vehicle control. An amber ABS warning light, when illuminated, indicates a fault in the anti-lock system. The brakes may still function in a basic, non-ABS mode, but stopping distances can increase on slick surfaces and the vehicle may be more prone to wheel lock if the driver does not adjust technique. The warnings reinforce the principle that braking safety is not a single action but a system of interdependent components. The driver must respond to these indicators with appropriate checks and adjustments, such as reducing speed and seeking maintenance if needed.

In everyday operation, the service brake pedal is a steady reference point for the driver. Its use should be smooth, deliberate, and well coordinated with other controls in the cab. The seamless integration of the pedal with the vehicle’s braking architecture means that a driver who interacts with the pedal consistently will experience predictable deceleration across a wide range of speeds and road conditions. The best practice is to apply moderate pedal pressure early in heavy traffic, allowing the ABS to manage the finer modulation as necessary. On long descents, a controlled, graduated brake input helps to avoid overheating the brakes and reduces the chance of brake fade. The driver can then rely on the vehicle’s transmission, engine braking, and, where present, regenerative braking to complement the service brakes, creating a layered approach to deceleration that preserves brake performance and reduces maintenance demands over time.

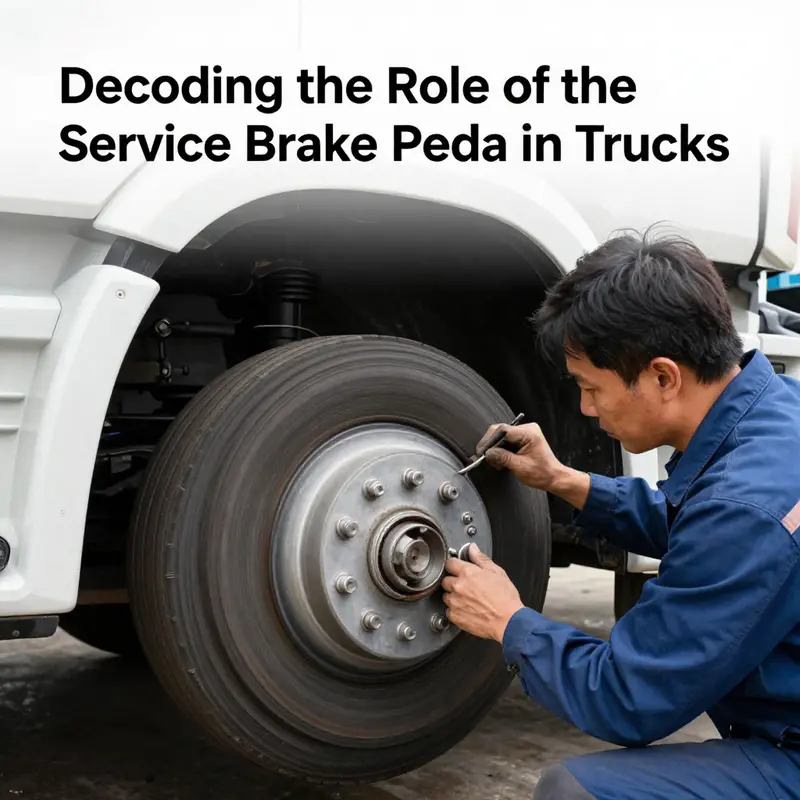

Maintenance and inspection are inseparable from how the service brake pedal functions in daily use. Drivers should be alert to any changes in pedal feel, such as unusual firmness, excessive travel, or a pedal that sits too close to the floor or too high above the floorboard. These cues can indicate air leaks in an air-brake system, worn seals in hydraulic circuits, or problems with the brake control valve. Leaks, worn pads, or contaminated brake fluid degrade braking effectiveness and can compromise safety at critical moments. Regular inspection of tires, brakes, and related components not only preserves stopping power but also ensures that the pedal’s travel remains within the designed range. Fleets that emphasize preventive maintenance tend to see fewer emergency brake events and more consistent deceleration performance. In this context, the driver’s awareness of the pedal’s behavior merges with fleet maintenance culture to create safer, more efficient operations. For fleets looking to strengthen their maintenance approach, recent industry observations underscore a growing emphasis on proactive brake system checks and sensor calibrations that align with the service brake pedal’s role in deceleration. See more in the updated trends surrounding private fleets trends in trucking maintenance.

To close the loop, the service brake pedal is not a mere knob but the physical manifestation of stopping power in heavy trucks. It is the locus where human intention, mechanical systems, and electronic controls converge. A driver’s steady, informed input translates through a network of brake components into predictable deceleration, whether on a congested urban corridor, a winding rural grade, or a wet slope. The pedal’s left-of-center position, its proportional force response, and the safety checks that surround it are all part of a decades-long evolution toward safer, more reliable deceleration. The driver learns to read the pedal’s feedback as a reliable guide through the complex choreography of friction braking, anti-lock modulation, and, in modern electric configurations, energy recovery that accompanies every stop. This holistic perspective helps explain why the service brake pedal remains the most critical round-the-clock control for truck braking, and why training, maintenance, and technology all revolve around its proper use. For those who manage fleets, understanding this single control’s full lifecycle—from input to feedback to maintenance—is essential to achieving safer roads, lower costs, and more predictable performance in every trip. External reference for deeper technical insight can be found in the Brake System Operation Guide.

The Pedal That Demands Precision: How the Service Brake Pedal Shapes Safety and Control in Heavy Trucks

The service brake pedal is more than a simple interface for slowing a truck. It is the primary control that translates the driver’s intentions into a reliable, reversible, and predictable deceleration. In the context of heavy trucks, especially articulated configurations that pair a tractor with one or more trailers, the pedal’s role becomes even more consequential. The mass and momentum of a fully loaded vehicle create a need for braking systems that respond with consistency, distribute force evenly, and preserve stability during a range of driving conditions. The service brake pedal, usually tucked to the left of the accelerator on the cab floor, is the driver’s direct link to this safety-critical function. When pressed, it initiates a carefully choreographed sequence that converts kinetic energy into heat, bringing the vehicle to a controlled stop and ideally preventing a collision or a dangerous loss of control. In this sense, the pedal is not merely a mechanical input; it is a crucial hinge in a complex safety chain that depends on precise timing, system integrity, and ongoing maintenance.

The heart of the matter is the way this pedal translates foot pressure into braking force, and the technology behind that translation has evolved significantly since early vehicles relied on cables and rods that could not reliably manage the loads generated by heavy trucks. In modern articulated trucks, most braking systems operate on hydraulic principles or, more commonly in heavy-duty fleets, pneumatic (air) systems that use compressed air to actuate braking power. In hydraulic configurations, pressing the brake pedal moves a pushrod or lever that activates a master cylinder, which converts mechanical input into hydraulic pressure. This pressure travels through a network of lines to slave cylinders or wheel cylinders at each axle. The result is an amplified force at the wheel brakes, so that a modest effort by the driver can generate substantial deceleration. The hydraulic pathway is designed to maintain consistent pressure across all wheels, ensuring even braking that reduces the risk of wheel lock or instability during heavy deceleration. The essential benefit is predictable, linear response: the harder the driver presses, the more braking force is delivered, up to the system’s designed maximum.

In air-brake configurations, which have long been the standard for heavy trucks, the pedal still serves as the primary input, but the mechanism of action is different. The pedal movement actuates a brake valve that modulates the flow of compressed air from reservoirs to brake chambers at each wheel. As the driver applies pressure, the valve adjusts air pressure in these chambers, causing the brake shoes or pads to engage with the drums or rotors. The system relies on the energy storage in the air reservoirs and the rapid, responsive control of the valve to achieve timely deceleration. In practice, this means the pedal’s action is intimately tied to the vehicle’s air pressure reservoir levels, the integrity of the airline network, and the condition of the brake actuators. Both hydraulic and pneumatic pathways share a fundamental objective: convert the driver’s foot effort into controlled braking torque at the wheels while maintaining stability and preventing wheel lock.

The design intent behind the pedal and its connected systems is to deliver uniform braking across the vehicle’s axle set. The brakes on the front and rear axles must be coordinated to avoid uneven deceleration, which could compromise steering control or lead to skidding on slick surfaces. In modern systems, brake force distribution is managed by valve logic and, in many cases, electronic control units that monitor wheel speed sensors and other inputs. The result is a braking experience that feels responsive yet stable, with the driver seldom needing to compensate for a sudden, unanticipated loss of braking power. This stability is critical when negotiating steep grades, merging with highway traffic, or performing evasive maneuvers during emergencies. In all of these scenarios, the pedal’s reliability becomes a cornerstone of safety rather than a mere convenience.

One of the most important aspects of the service brake pedal’s function is the way it interfaces with the vehicle’s safety systems. In articulated trucks, the braking system must account for the dynamics of a long, multi-element vehicle. The mass distribution shifts as trailers articulate and as load shifts during acceleration or deceleration. The pedal’s role, therefore, includes initiating not just a braking action but a balanced, coordinated slowing that respects the vehicle’s momentum, weight transfer, and stability envelope. When a driver presses the pedal, the system responds by increasing braking force in a controlled manner, smoothing deceleration and reducing the likelihood of abrupt weight transfer that could lead to a trailer swing or a jackknife situation. The physics of stopping a heavy vehicle are unforgiving: the energy that must be dissipated is enormous, and the pedal’s control mechanism is the interface through which this energy management is enacted.

The choice between hydraulic and pneumatic braking pathways is more than a technical preference; it is a reflection of how a fleet prioritizes reliability, maintenance, and fault tolerance. Hydraulic systems are known for delivering strong, linear braking response and a compact arrangement of components, which can simplify maintenance to some extent. However, the fluids and seals in hydraulic circuits must be kept free of air and contaminants to preserve performance. Pneumatic systems, on the other hand, excel in terms of fail-safety and redundancy; air brakes can operate with a robust reservoir system and multiple redundant lines. The pedal’s action in an air-brake setup must be tightly coupled to the compressor and reservoir health, because insufficient air pressure will dampen the pedal’s effectiveness, especially during sustained heavy braking or cold-weather conditions where moisture in the lines can cause icing or freezing. In either case, the driver’s input at the pedal is amplified by the system’s chosen architecture, and the outcome—braking power, pedal feel, and response time—depends on the ongoing health of that architecture.

A practical question for fleet managers and drivers alike is how the pedal’s performance translates into real-world safety margins. The driver judges distance, speed, weather, road grade, and traffic with a sensitivity that is anchored in the feel of the pedal and the vehicle’s braking response. When the pedal feels soft or has excessive travel before the brakes engage, there is a safety concern: it implies possible air leaks in a pneumatic system, degraded hydraulic seals, or worn brake linings. Such symptoms should trigger immediate inspection, because delayed recognition can allow heat buildup and brake fade to reduce stopping power. Conversely, a pedal that feels firm and consistent offers a reliable cue that the braking system is responding as designed, allowing the driver to anticipate stopping distances more accurately and plan lane changes or decelerations with confidence. In this context, the pedal’s feel becomes an early warning signal and a form of tacit communication between the vehicle and the operator about the state of the braking system.

Beyond the mechanics of stopping, the pedal is integral to how a driver negotiates emergencies and unexpected hazards. Emergency braking requires not only adequate brake force but also a stable deceleration that preserves steering control and minimizes the chance of wheel lock or trailer sway. In vehicles equipped with anti-lock braking systems (ABS) and electronic stability features, the pedal input is complemented by control algorithms that modulate braking pressure to prevent wheel lock. ABS works by cycling brake pressure rapidly to all wheels when it detects impending lockup, maintaining steerability and direction control. The driver may notice a pulsating feel through the brake pedal during ABS activation, which is an indicator that the system is actively protecting the tires and maintaining directional control. This interaction between pedal input and electronic safety features exemplifies how the pedal remains central even as braking technology becomes increasingly automated and sensor-driven. The result is a braking experience where human judgment and machine precision converge, with the pedal serving as the starting point for a cascade of safety responses.

Maintenance and inspection are inseparable from the pedal’s effectiveness. A robust safety culture treats the brake pedal as a system with many interdependent elements. The pedal pad itself must be intact and free of wear so that foot traction remains reliable. The pedal pivot and mounting must be secure, without looseness that could introduce delay or misalignment in actuation. For hydraulic systems, leak checks, fluid level assessments, and reservoir integrity are essential. Air brake configurations demand attention to compressor function, reservoir pressure, and the absence of moisture or contamination in the lines. Regular inspection extends to the brake drums or rotors, wheel cylinders or calipers, and the brake linings or pads. The goal is to minimize any factor that could elongate travel, reduce pressure, or compromise heat dissipation during extended braking. In a practical sense, a driver who senses soft pedal travel, unusual vibrations, or inconsistent braking feel should report these cues promptly, allowing technicians to identify issues such as worn linings, glazing, misadjustment, or air leaks before they escalate into a failure in a critical moment.

The quiet complexity of the pedal’s function often goes unseen by the casual observer, yet it governs one of the most consequential moments on the road: the moment a truck must stop to protect life and property. The more a fleet invests in understanding the pedal’s role, the more it can align maintenance schedules with real-world risk factors. Driving demands that operators remain attentive to how the pedal responds under varying loads, speeds, and road conditions. This conscientious approach reduces the likelihood of abrupt stops that could endanger the driver, passengers, or other road users. It also supports efficient fleet operations by preventing unscheduled downtime caused by brake system failures. In this light, the pedal is not a single component but a gateway to a broader safety ecosystem that includes brake systems, chassis dynamics, tire condition, road grip, and operator competency.

To connect these ideas to the larger industrial landscape, consider how maintenance priorities are shifting as fleets navigate evolving economic pressures and regulatory expectations. The same forces that drive investment in new fleets or updated routes also influence how maintenance budgets are allocated for braking systems. The emphasis on reliability, uptime, and predictable maintenance costs makes a strong case for proactive brake system inspections and the use of quality components in the service brake path. Fleet managers who monitor braking performance, track wear indicators, and schedule preventive maintenance create a more resilient operation, where the pedal’s reliability translates into fewer late-night calls, fewer roadside repairs, and a reputation for safety and dependability. This perspective aligns with broader industry analyses of strategic trends shaping trucking, including how maintenance practices adapt to shifting costs, labor markets, and the pace of technological change. For those looking to place these ideas within a broader economic context, a discussion of key economic trends impacting the trucking industry offers a useful frame of reference. key economic trends impacting the trucking industry.

As the field evolves, the service brake pedal remains a touchstone for driver skill and system design. It is the point at which human intent intersects with engineered safety. Its proper function depends on a chain of trustworthy components—from the pedal itself and its mounting to the brake valve, master cylinder or air brake components, reservoir integrity, and the wheel actuators. Each link must perform under the demands of daily operations, seasonal changes, and the unpredictable conditions of the road. The pedal’s reliability underpins everything from routine city driving to long-haul trips through challenging terrains and weather. It is a reminder that safety in trucking is not the result of a single clever feature but the outcome of an integrated, meticulously maintained braking ecosystem that starts with the pedal and ends with the wheels gripping the pavement in a controlled, stable stop.

For readers seeking deeper technical context, several authoritative resources outline the broader mechanics and engineering principles behind articulated truck braking systems. While the precise configurations can vary by make, model, and regulatory region, the underlying physics and safety implications remain consistent: a robust pedal mechanism, properly tuned brake control hardware, and well-maintained hydraulic or pneumatic pathways together create a deceleration experience that the driver can depend on. In practical terms, this means routine checks, early detection of wear, and a proactive approach to maintenance. It also means recognizing that the pedal’s effectiveness is contingent on the health of the entire braking chain, including the reservoir, lines, actuators, and wheel assemblies. When the pedal and its system are functioning harmoniously, drivers gain not only stopping power but also the confidence to manage real-world driving challenges with precision and composure.

In closing, the service brake pedal is a deceptively simple interface that sits at the nexus of driver skill, mechanical design, and road safety. Its operation—whether through hydraulic amplification or air-pressure modulation—serves a fundamental purpose: to convert a grounded foot press into controlled, safe deceleration. The pedal’s effectiveness depends on proper design, regular maintenance, and awareness of how the braking system interacts with the vehicle’s stability controls. For fleets and operators, appreciating this relationship means investing in regular inspections, timely replacement of worn components, and a clear understanding that braking safety is not a static feature but a dynamic, ongoing commitment. The pedal—and what lies behind it—embodies the principle that stopping power is as much about system integrity as it is about force applied at the moment of deceleration. And in a world where every mile can present unforeseen hazards, that commitment to reliability is precisely what keeps drivers and the public safer on the roads.

External reference for further technical depth: Understanding Articulated Truck Braking Systems. https://www.cat.com/en/technical-manuals.html

The Pedal at the Heart of Stopping Power: Mastering the Truck Service Brake Pedal

The service brake pedal sits in the cab like a calm, predictable trigger for one of the truck’s most critical safety systems. When the driver presses it, the immediate impulse is familiar: the brain signals a stop, the foot acts, and the vehicle responds. Yet behind that action lies a complex chain of mechanical and fluid dynamics that must stay reliable under a wide range of loads, speeds, and road conditions. In heavy trucks, the service brake pedal is the interface between human intention and a system designed to convert that intention into controlled friction at the wheels. The result should be a smooth, predictable deceleration that preserves control, minimizes risk to others, and avoids jolts that could unsettle cargo or passengers. The pedal is a safeguard woven into the rhythm of long-haul operations and urban logistics.

To understand why maintenance and troubleshooting deserve careful attention, a quick walk through the system helps. In many heavy trucks, the service brakes rely on air pressure to actuate brake chambers at each wheel. In hydraulic or mixed configurations, the pedal translates into a request for braking, triggering a sequence that reduces wheel speed. In an air-brake layout, the pedal position informs a valve assembly and a relay that modulates air pressure to the brake chambers, which then apply the brakes through pushrods and clevises that convert pressure into braking torque. The whole sequence depends on precise linkages, seals, springs, and fault-free lines. When any element drifts, the pedal delivers a telltale sign: extra travel, a softer feel, or a pedal that does not return smoothly. That sensation is a warning that the braking system’s integrity is at risk and deserves attention before a hazardous situation develops.

Maintenance begins long before a warning light; it starts with regular inspection of the pedal assembly and its surroundings. Visual checks can catch wear in the linkage, loose mounting bolts, and excessive pedal travel. A key indicator is pedal return: if the pedal lingers after release, there may be a binding point, a weak return spring, or a misadjusted pedal. The feel test and travel measurements help reveal air in lines, moisture, leaks, or worn components. In the broader system, moisture management for air brakes or fluid quality for hydraulic brakes keep the actuation reliable. Routine checks include listening for hissing leaks, inspecting hoses for wear, and ensuring lines are free of obstructions.

Troubleshooting follows a methodical path: verify smooth pedal travel, check return action, and diagnose any binding in the linkage or mounting hardware. If leaks exist, locate them and repair or replace components while following torque specs. Worn parts should be replaced with correct torque and re-torquing after initial system firings. A degraded pedal signal can also affect anti-lock and stability controls, so pedal readings must be considered as part of the whole braking network. The manufacturer’s service manuals offer model-specific diagnostics and torque specifications that help ensure safety and warranty coverage. For deeper grounding, consult the Brake System Operation Guide linked by technicians seeking a broader technical reference.

Contextually, a reliable service brake pedal supports fleet reliability, uptime, and safe operation across long hauls and urban routes. It sits at a critical junction between human judgment, machine safety, and vehicle dynamics, illustrating how small mechanical interfaces can anchor a broader system of safety and efficiency. For broader fleet management perspectives, related discussions on maintenance trends provide useful context for how organizations organize inspections, parts, and training to maintain predictable braking performance. The key takeaway is clear: treat the service brake pedal as a vital safety node, keep it well maintained, and address any signs of wear or softness promptly to preserve control in all operating conditions.

Final thoughts

Understanding the service brake pedal’s role is imperative for anyone in the trucking and logistics industries. From ensuring safety to guaranteeing effective vehicle operation, this component is a cornerstone of safe transportation practices. Regular maintenance and awareness of its functionality can significantly enhance safety and performance, benefitting not only operators but also businesses reliant on heavy-duty vehicles for their logistical operations.